The Two Types of Pu Er

Sheng Pu (Raw Pu Er): Officially a green tea, it is made in a classic green tea method. It is pan-fried at a lower temperature to allow some enzyme to continue to “live” in the loose leaf tea leaves and continue the fermentation process later.

Shou Pu (Cooked Pu Er): This is made by fermenting the already made Sheng Pu with added heat and moisture to facilitate “compost” of the leaves with assistance of beneficial microbes, making it a black tea.

Aging Pu Er

Both types of Pu Er can be aged. However, a common misconception is that Shou Pu is an “artificially aged” Sheng Pu. This is not correct. They are different teas and Sheng Pu aging does not result in Shou Pu. Sheng Pu is to complete the enzymatic metabolism of the leaves, eventually become similar to red tea. Shou Pu will continue to decompose whilst the bacteria in the tea continue to break down the leaves.

China has never had a tradition of aging tea.

A Pu Er’s aging potential does not mean the same with a Pu Er’s age. In other words, a cheap Pu Er does not become an expensive Pu Er merely by being old, just like a $10 bottle of wine’s value does not appreciate if being held for a few more years. One ages Grand Cru Burgundy, not Yellow Tail.

Pu Er Desirability: Tea Tree Age & Location

Tea Tree Age: Sheng Pu desirability is directly tied to the age of the tea trees. Highly sought after Pu Er come from trees 200-600 years old planted during Ming and Qing Dynasty, often referred to as da shu cha or gu shu cha. Sheng Pu from newer tea trees planted following traditional practice with prospect for the trees to be independent of human shaping and become big trees is called xiao shu cha. Majority of Pu Er come from newly planted bush tea trees in high density called tai di cha. Organic Pu Er is referred to converted tai di cha. Though pressed Pu Er is common, both kinds are sold as loose leaf tea as well. Traditional pressed Pu Er are in shapes of cakes and bowls. Standard cake weight is 357 grams. It’s also worth noting that even though there’s an impressive amount of old tea trees left from Ming and Qing Dynasty, an overwhelming majority of Pu Er produced nowadays are from plantation teas, which do not have a value for aging potential.

Terroir and Origin: Like all other Chinese teas, Pu Er's desirability will always be related to the tea's origin. The price difference between a $100 tea and a $1000 tea is the location. Therefore, it is essential to know the existing location division and how Pu Er connoisseurs regard them. All of China's historically famous teas have gone through an exercise of location specification pushed by its devoted connoisseurs. While many historical teas were endorsed and have stabilized terroir hierarchy by generations before us, Pu Er was not. From location hierarchy; to varietal to soil composition, refining processing techniques, we are the generation to figure Pu Er out and hopefully build a foundation for the future tea connoisseurs to appreciate Pu Er at a new level of sophistication. Hopefully, we do well.

The Three Main Regions

There are three Pu Er producing regions in Yun Nan. The names can be confusing - each often has interchangeable names and is sometimes called by its most famous inner region. However, it is crucial to be familiar with these regions, just as a wine enthusiast needs to know its terroir. Whenever you encounter a Pu Er name, try to see how it fits into the location; this will build a good conceptual understanding of the terroir over time. Remember, Pu Er specifications are still in development, so we are covering a vast region about the size of New York State.

1. Jing Dong: Wu Liang Shan - Ai Lao Shan (景東: 無量山-哀牢山)

2. Lin Cang: Meng Ku (臨滄: 勐庫)

3. Xi Shuang Ban Na (Jing Hong): Meng Hai - Meng La 西雙版納(景洪):勐海 -勐臘

Jing Dong: Wu Liang Shan - Ai Lao Shan (景東: 無量山-哀牢山)

Jing Dong Wu Liang Shan tea region is also sometimes called the northern tea region to the north of Ban Na. Jing Dong is the city's name, and the two most essential tea mountains in the area are Wu Liang Shan and Ai Lao Shan.

It's important to note that both mountains have large protected forest areas, harboring almost 1/3 of China's endangered species, making them essential for more than just tea. Especially Wu Liang Shan, which is also geologically significant; technically, the famous 15 tea mountains in Ban Na are all part of this mountain range at the southern end.

Wu Liang Shan has long been praised for its beauty and magnificence throughout history and popular culture. Wu Liang Shan can have the best value for Pu Er with the proper access because its market value is way below comparable-age trees from other regions. Old tree Pu Er here often selling for as much as small tree Pu Er in other regions' famous villages. It is also notorious for having the most plantation teas. The Pu Er from this region is usually sold under Wu Liang Shan or Ai Lao Shan, with no specific labeling of villages, making them unrecognized in the market. Wu Liang Shan Pu Er is known for being overall light, woodsy; without too much of a singular character, Wu Liang Shan can age to a prominent dry apricot sweetness. It has great value if one can find a reliable source for old trees.

Lin Cang: Meng Ku (臨滄: 勐庫)

Lin Cang is also sometimes called the western tea region, as it is West of Ban Na. It's important to point out that Lin Cang is the city, and Meng Ku is a "lower" level jurisdiction under Lin Cang, like a county. In the tea profession, the "lower" or the more specific the location name, the more valuable the tea. In the most unembellished language, Ling Cang's tea is cheaper than a tea called Meng Ku, which is cheaper than a tea called Bing Dao, which is cheaper than a tea called Bing Dao Old Village (Bing Dao, Bing Dao). This structure applies to all Pu Er and ALL other Chinese loose leaf teas. There's a river called Nan Meng/Mei River or Meng Ku Big River dividing Meng Ku county to east and west sides. There are 16 jurisdiction villages in Meng Ku. Borders of townships and villages are not always in line with tea tree coverage, so connoisseurs have divided up Meng Ku into the following 18 representative villages, with many even further specified into micro-terroirs.

East: Mang Bang, Ba Nuo, Na Jiao, Bang Du, Na Sai, Dong Lai, Mang Na, and Cheng Zi

West: Bing Dao, Ba Ka, Dong Guo, Da Hu Zhai, Xiao Hu Zhai, Bang Gai, Bing Shan, Hu Dong, Da Xue Shan, and Gong Nong

The most famous village of Lin Cang tea is Bing Dao (冰島, previously 丙島/扁島), and is currently one of the highest and most volatile Pu Er in terms of price (300% swing in some years). Bing Dao, the name of the jurisdiction village, consists of five natural villages, including one village also called Bing Dao, which is some times referred to as Bing Dao Old Village (冰島老寨). Simply put, Bing Dao is expensive, Bing Dao, Bing Dao is very expensive. The five Bing Dao villages are (also further divided by the river):

West: Bing Dao 冰島, Nan Po 南迫, Di Jie 地界East: Ba Wai 壩歪, Nuo Wu 糯伍

Ba Nuo壩糯: Ba Nuo is known for a unique kind of Pu Er called vine tea 藤條茶, named after its vine-looking shaped branches. The tea trees in this area have such an unusual shape because of the unique picking practices adopted by the farmers. They pick all the leaves on a branch except the ones at the end, encouraging the tea branches to grow longer and extend towards the direction of the remaining tea leaves. The overall east side of Meng Ku is known for vine tea trees, but Ba Nuo is the most representative.

Xi Gui 昔歸: Though this village is not in Meng Ku, Xi Gui has risen to be the second most expensive Lin Cang Pu Er, next only to Bing Dao, Bing Dao. The tea mountain is called Mang Li 忙麗 and is within the jurisdiction of Bang Dong 幫東, so there are also teas in the market using these names as references. But still, the more specific the location, the more worth mentioning it is. Overall, other than a few villages specifically discussed above, Lin Cang teas are sold under Lin Cang, or Meng Ku, as most individual villages do not have wide market recognition as their label. On average, the Lin Cang teas are less expensive than Ban Na's but more costly than Wu Liang Shan. The Lin Cang region Pu Er is known for being sweeter and brighter than the other regions with a thinner body and is more tannic. Lin Cang Pu Er is usually rubbed a little more between the hands or against the wok during the making process to help smooth out some of the rougher tannins.

Xi Shuang Ban Na (Jing Hong): Meng Hai - Meng La 西雙版納(景洪):勐海 -勐臘

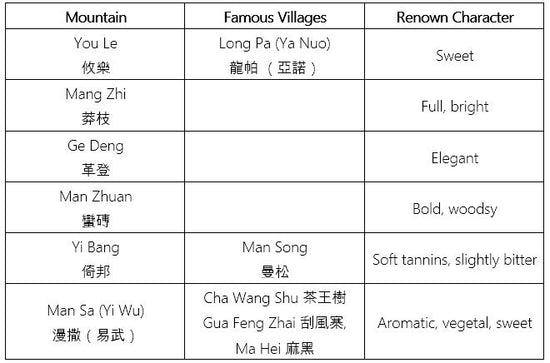

Xi Shuang Ban Na is often just shortened for Ban Na and is home to the famous 15 tea mountains. The mighty Lan Cang River divides the area into the West and East side, and Pu Er connoisseurs usually have strong preferences about which side they prefer. For a while, the tea mountains in the Meng Hai – Meng La areas were called the New and Old Six Ancient Mountains (yes, that's 12 total). If you are befuddled by the term "new ancient mountain," you are not alone. For reasons we are still not clear today, the historical records about Pu Er planting and trading back in the Ming and Qing Dynasty through tea-horse road are all about the Six Ancient Mountains to the east side of the river. And that's what keeps these mountains at the top of the Pu Er hierarchy. However, a survey of the land and archaeologically discoveries in modern time points to equally sizable organized tea planting and trading activities in the west side of the river in the Meng Hai area. So, to credit the Meng Hai mountains with the Ancient Mountain title they deserve, but to differentiate the already well-known Six Ancient Mountains, the term New Six Ancient Mountains was coined.

Why six and not nine?: Because the Chinese like symmetry. Throughout the 90s and 2000s, there has been debates about whether we should call the west side nine mountains or six mountains, as many argue that though some mountains are small, their tea exhibit highly distinguishable flavor profile and really shouldn’t piggyback on a bigger mountain’s name - certainly not for the sake to maintain symmetry. It really is only in the past 3-5 years that people have started to refer to the west side as nine mountains instead of six. This did change the dynamics in the Pu Er market and pricing. It’s worth noting that though there are only 7 mountains in Meng Hai, Jing Mai Mountain is not even part of Ban Na now. Tea professionals still conventionally refer 9 mountains as the Meng Hai tea. Similarly, on the east side, though You Le is not part of the Meng La jurisdiction, it is conventional being included when people are referring to Meng La tea. These 15 mountains now demand the highest price in the Pu Er market and each mountain has loyal fan followings to its unique characters.

-

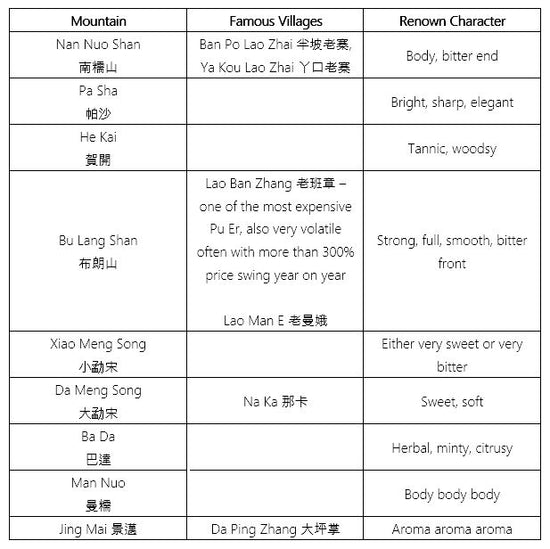

West Side of the Lan Cang River

Overall the west side tea is known for having more body than any other region’s Pu Er and a more substantial profile. Note that some mountains are small, therefore the whole place is well known without being specified to villages. There are also a few villages that are not exactly part of the 9 mountains, but have made names for themselves and are very well known.

-

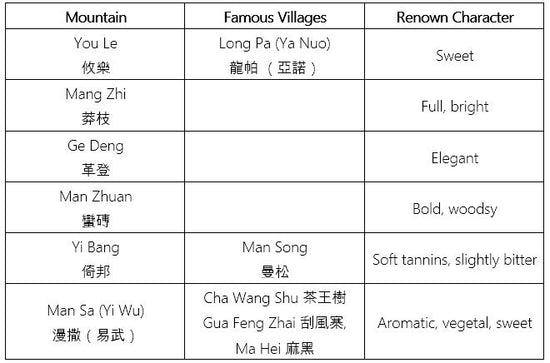

East of the Lan Cang River

Overall the east side teas are known for being softer, more expansive in the mouth feel with a permeating character that goes down deep. These are the old blood Pu Ers. Note that some mountains are small, therefore the whole place is well known without being specified to villages.

-

Bang Pen 班盆/邦盆

On the way between He Kai and Lao Ban Zhang, technically part of Bu Lang Shan range but not classified as so. The tea is known to be bright in taste, but also deep in mouth feel. It is very highly sought after.

-

Mang Jing (Weng Ji) 芒景(翁基)

Right next to Jing Mai, the taste profile is very comparable to Jing Mai, but a little more “shy”. It’s a distinguished ancient tea tree formation.

The Three Eras of Planting

-

The First Era: Tea as a Vital Part of the Local People (800-1800 years ago)

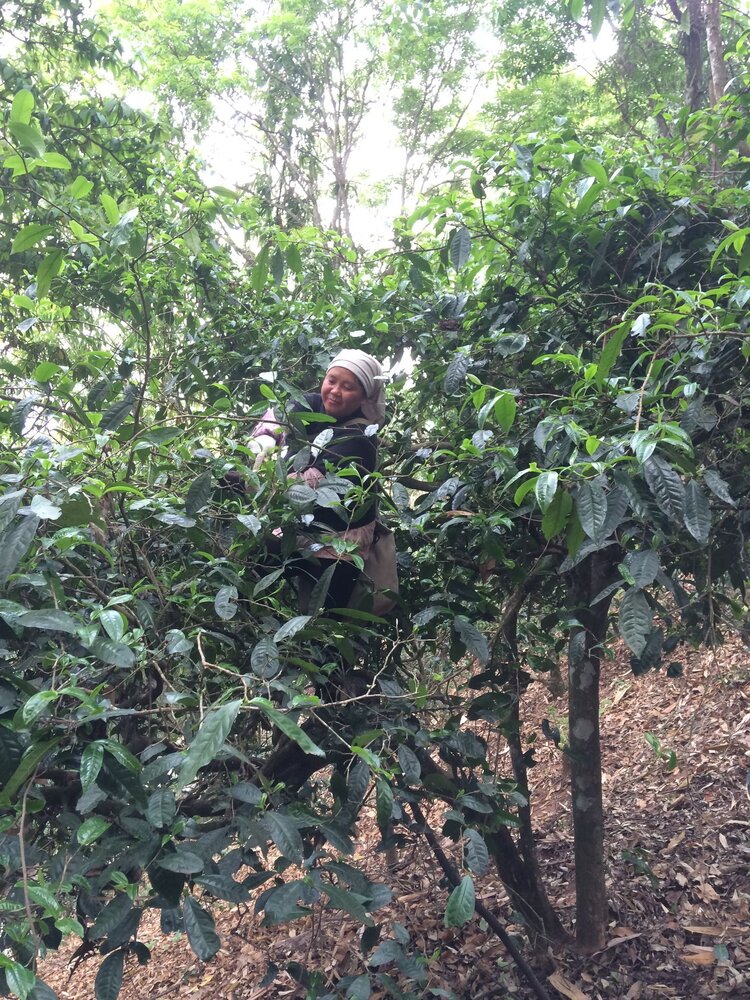

Yun Nan Province is home to about 30 different ethnic groups including the Thai, Ha Ni, Yi, Ji Nuo, Bu Lang, peoples etc.

Most of these cultures have a long tradition of cultivating and making tea with history going back as far as 1800 years ago. In 1950, when an official count was done, there were still 20-500 acres of very old tea trees, planted by the ancient ancestors of these indigenous people in varies mountains in southern Yun Nan, many are over 1000 years old. Only a fraction of them are still alive today, but almost every village has a few tea trees from this era and they are often crowned as the king tea trees. Teas from these trees are rare and often protected.

-

The Second Era: Tea as a Large-Scale Government Sponsored Activity (years 1415 – 1913)

Even though there has been private trading of tea for horses from Tibet and Si Chuan since the 1100s, it was not until Ming and Qing Dynasty that a large scale organized activity of tea planting and official trading for horses started. It has long been considered a brilliant political policy by historians: as a measure to cover war needs of horses; to maintain attachment of Tibet; to unite a very diverse boarder region; and to increase tax for the central government. The record in 1950 shows that there were still over 100,000 acres of tea trees from this era. Today, that number has been reduced to half - of which about 30,000 acres are from Ming Dynasty, mostly in the Meng Hai/Meng La region (15 Ancient Mountains). The highly desired old tea trees and big tea trees are usually from this era.

-

The Third Era: The Pu Er Bubble

Due to war and a series of unfortunate events, large scale tea production of Pu Er halted for most of the first half of 1900s. After 1950, there were some organized tea efforts, but very minimal. Pu Er started to surface the market again in late 1990s, but it was not until 2003 that producers paid any real attention to Pu Er.

- By 2005, Pu Er was the talk of the industry.

- By 2007, Pu Er prices had increased more than 100 to 6000 fold; many claimed it as the most valuable investment one can make.

However, in 2007, the “Pu Er Market” crashed and price dropped drastically. This is known as the Pu Er Bubble.

-

What Was The Pu Er Bubble?

Building up to the Pu Er Bubble, large amount of older tea trees were cut off to move space for the plantation teas known as Tai Di Cha. Not only were many low quality Sheng Pu produced to meet the demand of an irrational market, many Shou Pu were also produced and sold as an “aged” Sheng Pu. These low quality teas are still circulating in the market, and a large quantity of them were sold off to Hong Kong, Korea and the US. 2009 is often referred to as the year that Pu Er started to be “professionalized,” where the producers demonstrated more expertise and consumers became more educated. The Pu Er phenomenon had kick-started a new aging practice in Chinese tea drinking, which was NOT a tradition in China before.

Yi Wu Mountain

It is important to know that Yi Wu back in the day, refer to a much larger region than what Yi Wu sometimes today means, hence the term Yi Wu Zheng Shan, or THE Yi Wu Mountain. Technically, all of the six ancient mountains nowadays are part of Yi Wu except You Le. That’s why a lot of the older books only discuss the preference between Yi Wu and You Le. The nowadays-narrower definition of Yi Wu, or THE Yi Wu Mountain, is referring to Man Sa. This can be very confusing because even today, the habits of using Yi Wu varies - every year we encounter people who wanted to go to Yi Wu (Man Sa) but ended up in Ge Deng or other mountains. To illustrate how confusing Yi Wu does not equal Yi Wu is, the most “noble” Yi Wu, Man Song, is actually in today’s Yi Bang, not THE Yi Wu Mountain, which again, is Man Sa. Overall, Yi Wu is the most expensive mountain on the east side and, similarly to Jing Mai on the west side, is known for its unique aroma. Also, some of the most expensive Pu Er in today’s market are those from the National Forests in the greater Yi Wu area. Very recently, the government allowed the nearby farmers to harvest these tea trees in change for their stewardship of the trees and its natural habitat. Because these tea trees are ancient and essentially wild, they are highly sought after. These are the most expensive Pu Ers in the last three years with fresh leaves selling for as much as $2000/lb. (And keep in mind it takes at least 4lb leaves to make 1lb tea). Notable locations are Wan Gong 彎弓, Bo He Tang 薄荷塘, Ding Jia Zhai 丁家寨, Yi Shan Mo 一扇磨, Bai Cha Yuan 白茶園, and many more but each with very small amount of harvest. This started a wave of discovering tea trees in varies National Forests in hope to become the next goldmine.

Travels to Yun Nan

Pu Er Varietals

Pu Er varietal is actually very simple because it is not specific. Due to the new-to-fame status of Pu Er, intricate details such as tea tree varietals are yet to be studied thoroughly and now they are mostly just called Yun Nan Big Leaf Varietals. But, we do see a lot of varietals, especially in the higher and colder mountains in the Meng La region, resemble characteristics of a small-leaf varietal. Some of the most valuable Pu Ers such as Ge Deng are now unofficially classified as small-leaf varietals. Unique tea trees such as the vine-shape tea trees are also yet to be studied further to see if there’s a cause-effect connection between its biology and the unusual picking style the people adopted.

Pu Er Production

Pu Er making follows a very typical green tea process, that’s why it is academically classified as a sun-dry green tea. Pu Er picking is usually one bud with two-three leaves. The teas are usually shade wilted to lose some moisture before being wok fried in large batch. The large batch of Pu Er being processed each time is the “mistake” that cause the tea’s enzyme not being damaged thoroughly, providing the basis for aging Pu Er later on. The hot and moist tealeaves are then rolled and shaped quickly before being evenly spread out under the sun to dry. Aggressively strong sun is the most preferred in Pu Er making. There’s a price difference between one-day dried Pu Er and two-or-multi-day dried Pu Er.